Antonín Dvořák

Born: September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, Bohemia

Died: May 1, 1904, Prague

Concerto in A Minor for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 53

- Composed: 1879

- Premiere: October 14, 1883 by violinist František Ondříček

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: December 1903, Frank Van der Stucken conducting, Emile Sauret, violin

- Most Recent: September 2013, Ignat Solzhenitsyn conducting, Anne-Sophie Mutter, violin

- Most Recent Subscription: December 20211, Andrew Grams conducting, Ray Chen, violin

- Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

- Duration: approx. 32 minutes

Some works of art seem to spring from the imagination of their creators immediately, with little effort. Others must first gestate for months or years, and then be coaxed out into the world through long, painstaking labor. In 19th-century Berlin, the violinist Joseph Joachim saw himself as the midwife of this scenario.

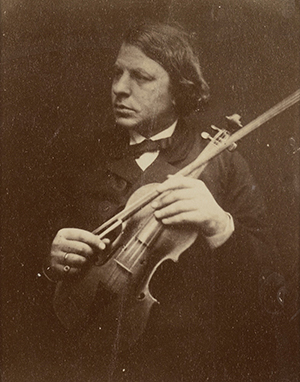

Joseph Joachim (1831-1907)

Joachim was not only one of the most distinguished violinists and pedagogues of the late 19th and early 20th century; he was also a significant influence on several masterworks of the violin repertoire. He worked directly with many of the greatest composers of his day: he maintained cordial, professional relationships with Max Bruch and Felix Mendelssohn; he advised Robert and Clara Schumann on how to best write for his instrument; and he enjoyed a close personal friendship with Johannes Brahms, whose violin concerto Joachim premiered. Joachim had a hand in the final edits of many of their works and promoted them from concert stages across Europe.

When the Berlin publisher Simrock commissioned a violin concerto from Antonín Dvořák, Joachim was the clear choice to premiere it. The two musicians had met previously in Berlin, where Joachim was the founding director of the Königliche Hochschule für Musik. Furthermore, Joachim had already premiered Dvořák’s String Sextet, Op. 48, and had toured London performing Dvořák’s string quartets.

So, in July 1879, Dvořák traveled to Berlin, where Joachim had organized a gala in his honor. Dvořák brought with him the early draft of his violin concerto, the title page inscribed, “I dedicate this work to the great Maestro Jos. Joachim, with the deepest respect, Ant. Dvořák.” The two studied the sketch and Joachim recommended some changes, which Dvořák integrated into the next version of the score. They met again the following spring to discuss further amendments, after which Dvořák began a complete revision. He wrote to his publisher, "Although I retained some of the themes, I have written several new ones. The whole concept of the work is changed, however. The harmonization, the orchestration, and the rhythms are new."

Joachim took this new version for study, but his enthusiasm seems to have waned; he made little progress on it for the next two years. He finally wrote back to Dvořák with suggestions for further changes, explaining that, while the concerto had many beautiful moments, the orchestration was too dense and the violin part too clumsy. In the meanwhile, Dvořák seems to have grown exasperated: he wrote to his publisher that he was “very glad that the matter has finally been sorted out. The issue of revision lay at Joachim’s door for a full two years!! He very kindly revised the violin part himself.”

After some adjustments to the orchestration, the work was submitted to the publisher, who then requested even further alterations, including shortening the third movement and providing a clear ending to the first movement to separate it from the Adagio that followed. Dvořák dug in his heels on this last request, rallying support from fellow violinist Pablo de Sarasate, and insisting on linking the first two movements, much as Mendelssohn and Bruch had done in their own violin concertos in previous decades.

In spite of the revisions, Joachim was not happy with the concerto, and he eventually sent the score back to the composer in 1882. Dvořák’s biographer, Clapham, speculates that the work may simply have been too radical a departure from classical ideals for Joachim’s conservative tastes. Dvořák completed a final round of edits before October 1883, when it was finally premiered in Prague by Czech violinist František Ondříček. Ondříček went on to introduce the work to audiences in London and Vienna.

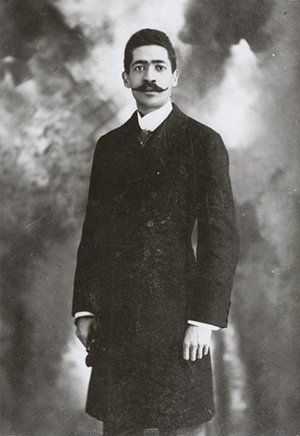

Will Marion Cook

Joachim and Dvořák seem to have remained on cordial terms, however, for they communicated indirectly over the next decade, particularly concerning their support of the African American composer Will Marion Cook. Cook studied with Joachim at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik for nearly a decade before returning, upon Joachim’s recommendation, to study composition with Dvořák in New York. Dvořák felt certain that the music of America’s various ethnic communities was its most valuable resource for the founding of a truly American musical tradition, and he cultivated a respect for those idioms in his students. Cook went on to establish himself as a professional composer, conducted several professional ensembles, and led the New York Syncopated Orchestra’s tour of England, where they performed for the royal family. His musicals for the New York stage were the first full-length theatrical works written and performed by African Americans that were allowed to play in prestigious Broadway houses.

Dvořák’s Opus 53

The Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 53 is both melodic and adventurous, filled with folk-like tunes and strong rhythms. Its structure departs from the norm: the first movement, Allegro ma non troppo, is cut short, which led early critics to criticize its lack of symmetry. But sacrificing form in favor of substance is a worthwhile trade-off: the concerto grabs the ear from its first notes and holds the listener captive throughout. Furthermore, Dvořák’s insistence on eliding the first movement into the second was a brilliant choice: without the release of tension that a decisive ending would have provided, it is the audience, not the soloist, who does the work of carrying the emotional intensity of the first movement over into the second.

The themes of the first movement establish the work’s Bohemian pedigree from the opening fanfare by means of strong dance rhythms. Dvořák tempers those with occasional touches that invoke the spirit of Brahms, such as the displaced ties across bar lines. The transition into the middle movement, Adagio ma non troppo, is accomplished through gentle motion as the flute and oboe settle down into a major key.

This middle movement again summons Brahms in its calm motion and its heightened expressivity. Long, lyrical countermelodies in the woodwinds complement the soloist as the harmonies shift in unexpected ways, sprinkled with exquisite touches of contrapuntal filigree. The movement builds to a full, rich, soaring string tune in parallel thirds—Brahms again!—before closing with another image from the Bohemian countryside: the main tune appears in the horns while the soloist accompanies with delicate arpeggios.

The finale, Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo, represents Dvořák at his finest. He opens with a furiant, a quick Bohemian dance with sharp, shifting syncopations that trick the ear into hearing 2/4 time, even though the music is truly in triple meter. Three longer episodes interrupt the main theme, and here, too, Dvořák invokes his homeland with drums and bagpipe drones. The centerpiece of the movement, however, is the sudden lapse into a dumka, a plaintive Slavic lament in moderate 2/4 that eventually returns to the main theme and leads to a rousing finish.

Throughout the violin concerto we see signs of Dvořák’s genius. The composer was brilliant at crafting folk-like tunes that sounded authentically home-grown to the ear, even though they were fully the product of his musical imagination. (The faux-spiritual hymn tune in his Symphony No. 9, From the New World is perhaps the easiest example to cite.) But we must also recognize the other strengths of the concerto, not the least of which are the ever-changing combinations in his instrumentation that create constant variety and color.

Postscript:

Dvořák’s concerto was championed by generations of violinists, including Josef Suk, Salvatore Accardo and David Oistrakh and has become one of the cornerstones of the violin repertoire. As for Joseph Joachim, he soon came to appreciate the artistry of the work, but he never did get to perform it in public. He eventually programmed it for a concert in England during Dvořák’s visit in 1884, but that performance became a point of contention between two conflicting concert societies and had to be cancelled. Yet, to this day, it is Joachim’s own fingerings and bowings that grace the Urtext edition of the work, a testament to his high regard for its charm and beauty.

—Dr. Scot Buzza