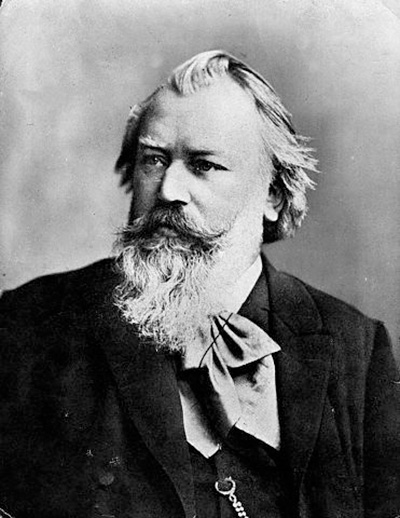

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

Symphony No. 4 in E Minor, Op. 98

- Composed: 1884–85

- Premiere: October 17, 1885, Meiningen, Germany, Johannes Brahms conducting

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: March 1900, Frank Van der Stucken conducting

- Most Recent: September 2019, Eun Sun Kim conducting

- Notable: January 1926 at Carnegie Hall, Fritz Reiner conducting

- Recording: Brahms: Symphony No. 4 released 1966, Max Rudolf conducting

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, triangle, strings

- Duration: approx. 39 minutes

Johannes Brahms often composed during the summer while residing in countryside retreats in Austria, Germany or Switzerland, including his fourth and final symphony, which he composed in the Alpine village of Mürzzuschlag, 60 miles southwest of Vienna. There, he completed the first and second movements during the summer of 1884 and the finale and scherzo (in that order) during the summer of 1885.

When creating new works, he often sought feedback from trusted friends. In this case, he shared his manuscript of the first movement with Clara Schumann (1819–96) and Elisabeth von Herzogenberg (1847–92), highly gifted musicians whose opinions Brahms greatly respected. They studied the score and played through it on the piano. While they were very excited by the prospects of a new symphony, they worried about the work’s complexity. Other friends, including the violinist Joseph Joachim (1831–1907) and the music critic Max Kalbeck (1850–1921), raised similar concerns. Although Brahms made numerous changes, including altering some of the dynamics and tempi and excising a chordal phrase he had initially envisioned as a brief introduction to the first movement, he did not substantially alter the passages his friends had discussed. Indeed, this was not unusual: at the height of his career, he often discounted the critiques of his most trusted friends. In some cases, he sought their opinions on specific sections of a new piece as a way of confirming to himself that he had considered all possible ideas and chosen the best ones.

After completing the entire symphony, Brahms arranged for trial performances at the court of the Duke of Meiningen, which was located in the southern part of the state of Thuringia in Germany. The Duke had a world-class orchestra that was renowned for its precision and clarity, and for its excellent players. Hans von Bülow (1830–94), its conductor, had previously put the orchestra at Brahms’ disposal so he could test out other new works. Brahms greatly appreciated this type of opportunity because it enabled him to assess whether the instruments were correctly combined and balanced, and whether the important melodies and motives could be clearly heard. After a few rehearsals, Brahms conducted the orchestra in the public premiere of the symphony. The Duke and his friends were so impressed that they asked for the first and third movements to be repeated. Despite this success, Brahms wanted to hear additional performances before publishing the score, which happened quite quickly because the Meiningen orchestra had already planned a concert tour. They gave more than 17 concerts throughout Germany and The Netherlands, most of which included the symphony, and Brahms conducted at least nine of those performances. During the tour, Brahms approved the score’s publication and, once it became available, other orchestras also began performing the symphony. His friend Hans Richter (1843–1916) led premieres in Vienna and London; Walter Damrosch (1862–1950) conducted the American premiere in New York on December 11, 1886; and, a month later, Theodore Thomas (1835–1905), the conductor who perhaps did the most to promote Brahms’ compositions in America, led a performance by the New York Philharmonic. Once Brahms’ friends heard excellent orchestras perform the symphony, they realized their previous concerns and objections were unfounded. After Joachim conducted the premiere in Berlin, he wrote to Brahms, “The really gripping character of the whole, the density of invention, the wonderfully interwoven growth of the motives have claimed my affection even more than the richness and beauty of its individual passages.” The symphony also won over numerous music critics, with one London writer praising the wealth of the melodic ideas of the first movement and noting that they were easy to remember.

The second movement, an Andante moderato, immediately appealed to many listeners and critics. Kalbeck, a close friend of Brahms who later authored the most thorough biography of the composer, was immediately captivated by its resonance and lyricism. While many listeners will be instantly drawn to the opening theme, which features the horns and winds, the second, yearning theme played by the cello is equally beautiful. Herzogenberg adored this melody from the first time she played it on the piano, and she was moved to “happy tears” when she heard the movement played by an orchestra. Later she wrote to Brahms, “It is a walk through exquisite scenery at sunset, when the colors deepen and the crimson glows to purple.” (While 19th-century musicians often used technical terms to describe music, they also used colorful prose, drawing on images from nature to vividly capture their response to a work.)

The third movement, marked Allegro giocoso, is the lightest of the symphony, but its pulsating rhythms, sudden pauses and, at times, harsh sounds caused some critics to consider it a grotesque joke. Brahms himself described it as “fairly noisy” because it included three timpani, a triangle and piccolo—an instrument Brahms rarely used, but one that is well suited to the movement’s carnivalesque tone. With its rowdy, furious mood, this movement provides a striking contrast to the others and is a suitable respite between the reflective second movement and the unabashed power of the fourth.

Brahms’ intense study of music dating as far back as the 16th century is well known. Older compositions provided him with a wealth of ideas and compositional techniques that he could transform in his own works. The Allegro energico e passionato, the fourth movement of Symphony No. 4, is one of the most famous examples of this. The movement is a passacaglia, a type of compositional technique dating back to before 1600 that involves varying a short theme. Brahms studied and admired how Bach employed this technique in his Chaconne in D Minor for solo violin (1717–20) and in the finale to his Cantata No. 150, “Unto Thee, O Lord, Do I Lift Up My Soul.” In addition to using the same passacaglia technique as Bach, Brahms created a main theme for the finale of his symphony that is very similar to the one Bach used in the cantata. His decision to use a type of variation form was likely also influenced by the variation movement that concludes Beethoven’s Eroica symphony. The main theme of Brahms’ finale is varied 30 times, but it never becomes boring because he combined it with new ideas and harmonies and drew on contrasting orchestral colors. Quiet passages, including a gently wafting flute solo and solemn chorale-like phrases intoned by the trombones and bassoon, contrast with the orchestra’s dramatic and, at times, anguished phrases. This spectacular finale has been accorded many accolades, with Kalbeck labelling it as “the crown of all Brahms variation movements.”

—Heather Platt, Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts and Professor of Music