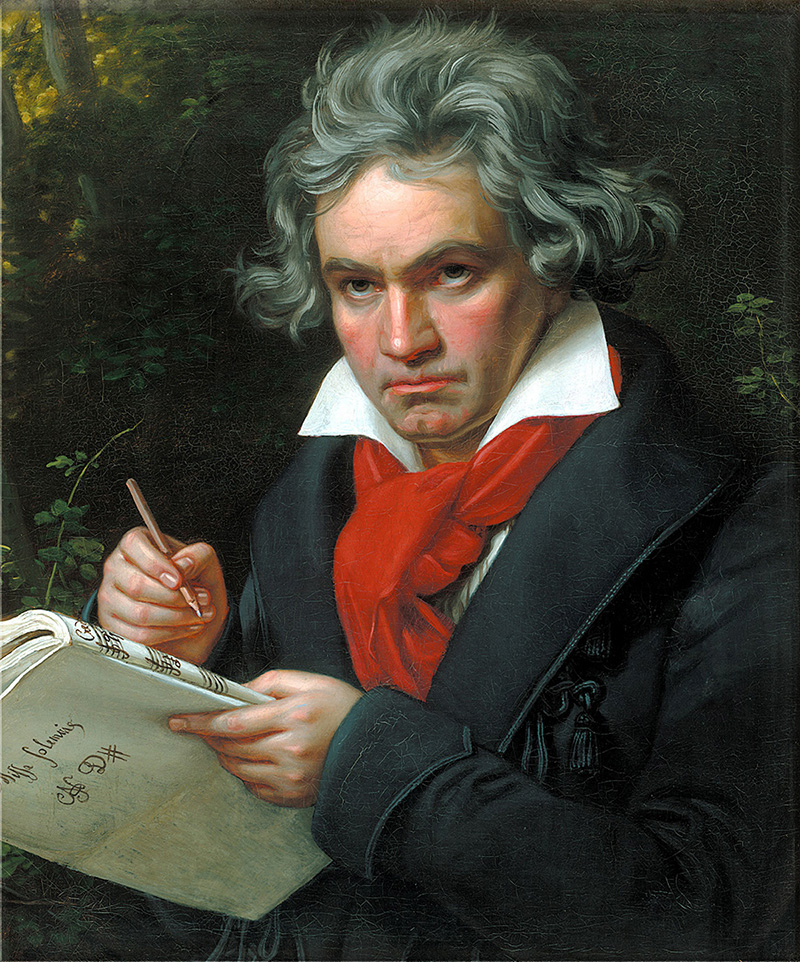

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born: December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Op. 55, Eroica

- Composed: 1802–04

- Premiere: April 7, 1805, Theater an der Wien, Beethoven conducting

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: January 1896, Frank Van der Stucken conducting

- Most Recent: February 2019, Louis Langrée conducting

- Recordings: Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 'Eroica' released in 1968, Max Rudolf conducting, and Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 'Eroica' released in 1981, Michael Gielen conducting

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 3 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

- Duration: approx. 47 minutes

Turn-of-the-Century Vienna

Beethoven despised Vienna and resented the Viennese. When he arrived at age 22, short on cash and over-endowed with ego, he expected aristocratic doors to open for him. When they failed to, he took it personally: “Verflucht, verdammt, vermaledeites, elendes Wienerpack,” he wrote, or, translated, “Cursed, damned, scourged, wretched Viennese low-lifes.” Meanwhile, political events in France had captured his imagination; he had been 18 years old when the storming of the Bastille occurred, and like many others his age, he found revolutionary ideals alluring. He soon began to plan his exit strategy, bartering with an agent to get his music published in Paris and help him leverage a position in France. It would have depressed him deeply to know that he would, in fact, never leave the Austrian capital.

Political Baggage

A careful look at music history shows that the quainter the anecdote, the less likely it is to be historically true. Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 has been saddled with several canards. One of the most famous, first reported by the composer’s secretary, Anton Schindler, alleges that the French general Bernadotte inspired Beethoven to compose a musical homage to “the greatest hero of the era.” This is improbable: Bernadotte had been in Vienna only briefly, five years before Beethoven began work on the symphony; furthermore, Schindler made a habit of fabricating stories about Beethoven to exaggerate his own influence and intimacy with the composer. Another legend about the Eroica comes from Beethoven’s physician, Bertolini, who told biographers that Beethoven’s funeral march in the second movement was an allusion to Napoleon’s march to Egypt and the rumored deaths of general Abercrombie and vice-admiral Nelson at the Battle of Abukir. Here too, the timeline makes no sense: the events referred to had taken place five years previous. The most persistent story, however, is that Beethoven had originally dedicated the composition to Napoleon with an inscription on the title page, but after Napoleon crowned himself emperor, Beethoven tore up the title page in a rage and yelled, “He is no different than an ordinary man! Now he will trample all human rights underfoot, indulge only his ambition; now he will place himself above all others, become a tyrant!” Although theatrical, this account is at least partially supported by evidence: the gouges and erasure marks on the title page of the composer’s manuscript, where the paper was scraped away (although certainly not torn up).

Beethoven's title page, showing the eradication of his dedication of the work to Napoleon.

Beethoven had indeed been initially fascinated and impressed by the ideals and achievements of the French general, but the history of his score to his third symphony demonstrates how that opinion flip-flopped repeatedly over the course of his career. After obliterating the original dedication, Beethoven had changed his mind again, reporting to the publisher Breitkopf & Härtel in August 1804 that “the symphony is actually entitled Bonaparte.” He vacillated again five years later, in 1809, when he added the subtitle “Heroic symphony composed to celebrate the death of an unknown hero” (“Sinfonia Eroica composta per celebrare la morte d'un Eroe” and later “per festeggiare il sovvenire di un grand'uomo”) to the London editions of the score. Changing his mind once more many years later, he penciled in “written on Bonaparte” at the bottom of the original title page.

Beethoven’s sympathies for the French Revolution were no secret. Upon his arrival in Vienna in 1892, he had purchased a subscription to Eulogius Schneider’s book of Jacobin verse, and his penchant for public, alcohol-fueled rants against politicians and clergy eventually attracted the attention of the emperor’s police. Nineteenth-century scholar Fan S. Noli pointed out:

“All the slogans of the French Revolution can be found in Beethoven’s writings and, sometimes, in places where we hardly expect them, in business letters and love letters. And it must be borne in mind that all those slogans were anathema to the old regime of Vienna, which considered them dangerous to the state and forbade their use to its citizens.”

Indeed, Beethoven’s support of the French Republic further fueled his disdain for Vienna and the Viennese. Resentful, he disparaged the city and its politics both in public and in his private letters (which were sure to be read by censors, in any case). He quietly plotted his move to Paris, which he was certain would be better, both personally and professionally. The move never came to pass: he eventually obtained a stipend to stay in Vienna from several Viennese aristocrats, including Prince Joseph von Lobkowicz, to whom he wrote a revised dedication to his Eroica symphony in exchange for 400 ducats.

The Theater an der Wien

Theater an der Wien, 1826

The Eroica premiered at Vienna’s Theater and der Wien in April of 1805, with the composer conducting. The sheer scale and length of the work was overwhelming to audiences, and the response of listeners was mixed. An anonymous review in Der Freymüthige summarized it:

“One group, Beethoven’s very special friends, maintains that precisely this symphony is a masterpiece, that it is in exactly the true style of more elevated music, and that if it does not please one at present, it is because the public is not sufficiently educated in the arts to be able to grasp all of its lofty beauties…. The other group utterly denies that this work has any artistic value.”

Beethoven himself was aware of the burden the symphony placed on the listener. He made it clear in an annotation, in Italian, printed in the first violin part of the original edition (translated):

“Since this symphony has deliberately been written at a greater length than is usual, it should…be performed closer to the beginning [of the program] than to the end…for it will lose its effect for listeners who will be exhausted by the preceding compositions.”

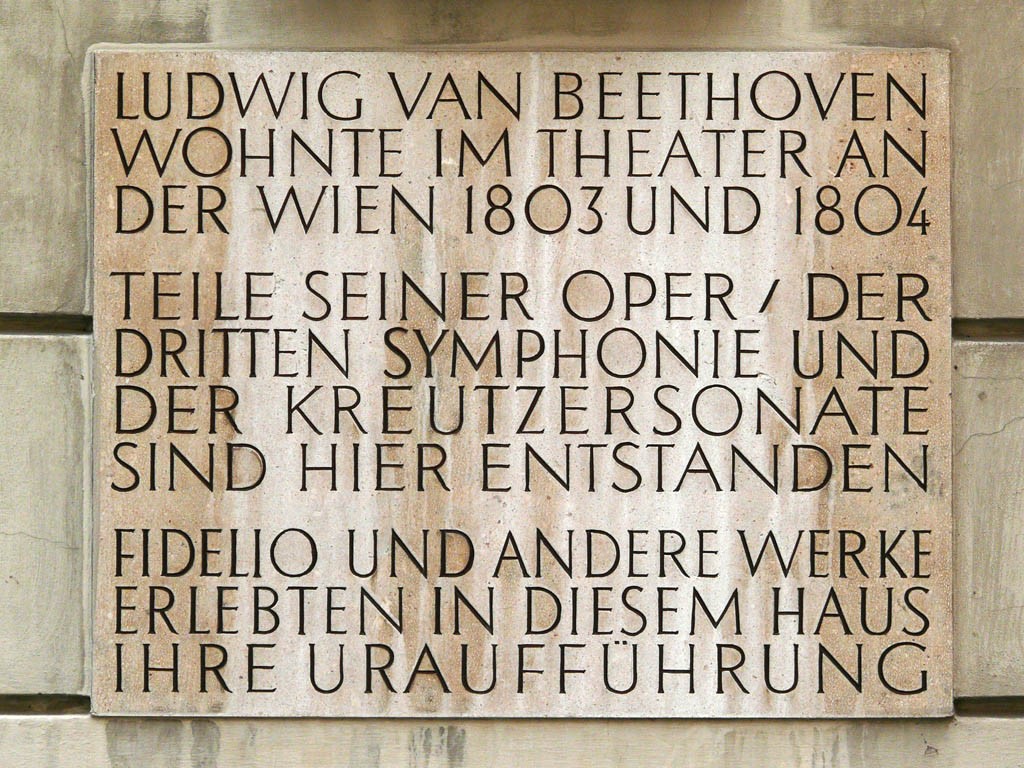

Beethoven memorial on the exterior wall of the Theatre an der Wien: "Ludwig van Beethoven lived in the Theater an der Wien in 1803 and 1804. Parts of his opera, the Third Symphony, and the Kreutzer Sonata were written here. Fidelio and other works received their first performance in this house."

The Eroica

The work required audiences not merely to listen passively but to focus on its musical content in a way that they previously had not. From the opening phrase of the first movement, the audience must “listen through” a much denser soundscape to discern melodies and harmonic twists of an uncustomary complexity. The manipulation of the opening triadic theme and its unexpected lurch into chromaticism lead to secondary themes spread throughout the movement, which then become the musical building blocks that Beethoven uses, in constantly changing ways, to extend the movement to a full 16 minutes or more. However, the composer also rewards the careful listener in several ways: with constant innovation, with some expectations fulfilled in a musically satisfying way, and other expectations blatantly thwarted, such as the famous “false entrance” from the horn player.

Hector Berlioz viewed the second movement of the Eroica as a brilliant, self-contained, one-act play in commemoration of the symphony’s eponymous hero. He commented, “I know no other example of music of a style wherein grief is so able to sustain itself consistently in forms of such purity and nobility of expression.”

Indeed, this march is not the quick two-step of military bands, but rather, a funeral cortège, briefly interrupted by a fugue, before the oboe takes up the theme. Berlioz wrote, “the wind instruments cry out as if it were the last farewell of the warriors to their companions-in-arms.”

Beethoven’s third movement is more than double the length of the corresponding third movements of his first two symphonies; it was unprecedented, but it created the template for the expansive symphonic scherzo that would then persist throughout the 19th century. He extends the usual three-part scherzo template with a coda consisting of a spectacular crescendo, building from pianissimo to fortissimo. His sketches show that this sensational effect had been conceived from the earliest stages of composition as the intended climax to the previous 15 minutes of music.

In the final movement, the composer recycled themes he had used several years previous, in his piano variations, Op. 36, as well as his ballet, Creatures of Promethius. Beethoven’s first sketches of the movement are headed “Variations” and “Fuga,” but the piece in its final form dissolves those distinctions into a fast-slow-fast structure followed by a coda that reiterates the previous themes before concluding with another theatrical outburst: a sudden crash and flurry by the orchestra, leading to three triumphant chords. The Finale failed to satisfy early audiences in the way that a more conventional rondo or sonata for might have, despite its genius and originality—or perhaps because of it. A reviewer for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung wrote that the composer “often wanted merely to toy with the audience without taking their enjoyment into account, simply to unleash a strange ambiance and, at the same time, to let his originality sparkle." Another moaned: “This Finale is long, very long….”

The Legacy

Nowadays it is difficult to imagine this symphony in any other form, because of its place of pride in the orchestral repertoire. However, it is easy to underestimate the intellectual achievement it represented and the excitement it caused in the early 19th century: it was bigger, louder, longer and denser, and it required much more concentration than what audiences were accustomed to. Small wonder that composers before him had been so much more prolific: Mozart had written more than 40 symphonies, Haydn more than 100. Yet, those who followed Beethoven would rarely compose more than nine or 10. In the Eroica, Beethoven effectively brought the symphony into the 19th century: a new standard was set, and the public notion of the genre was permanently changed. Spectacle, breadth, length and complexity were established as required elements. Beethoven had sacrificed immediate audience appeal in exchange for emotional depth, reconceiving the genre in a way that challenged the listener and took the symphony beyond mere entertainment, elevating it to the sublime.

—Dr. Scot Buzza