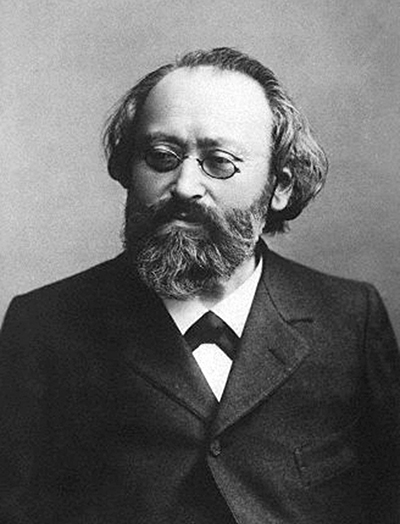

Max Bruch

Born: January 6, 1838, Cologne, Germany

Died: October 2, 1920, Friedenau, Berlin, Germany

Concerto No. 1 in G Minor for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 26

- Composed: 1865–66

- Premiere: April 24, 1866, Koblenz, Germany, with the composer conducting and Otto von Königslöw, violin

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: January 1897, Frank Van der Stucken conducting; Charles Gregorowitsch, violin

- Most Recent: September 2017 on tour in Utrecht, Netherlands, Louis Langrée conducting; Renaud Capuçon, violin

- Most Recent CSO Subscription: November 2015, Louis Langrée conducting; Renaud Capuçon, violin

- Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

- Duration: approx. 24 minutes

Max Bruch had an extremely long career. At age 11 he started composing. At age 12 he won prize money for his string quartet, which enabled him to formally study composition, music theory and piano in his native Cologne. At age 20 he completed his first opera, and at age 83 he wrote his last works. Yet it is his Violin Concerto No. 1, Op. 26, written in his 20s, that first launched him to international recognition, fueled an American scam and earned status as one of the jewels of the violin solo repertoire.

Prologue: Koblenz, Germany

In September 1865 Bruch was appointed to what he was sure would be his dream job: director of the Royal Institute for Music and of the Koblenz Subscription Concert series in Koblenz, Germany. He had elbowed out 49 other applicants for the job, which was deemed a plum post. It came with an orchestra of 60–70 musicians, mostly professionals, and a chorus of 150 singers. The director was charged with producing 10 concerts every autumn and winter and rehearsing the women’s chorus for six hours each week. The salary was fixed at 367 thalers—a princely sum for a 27-year-old—and the contract allowed for additional income through private teaching.

But more appealing still were the professional opportunities that came with the job title. It gave him a reason to hobnob with guest artists such as Clara Schumann, but it also provided him an opportunity to program his own compositions alongside those of more famous names, among them Mendelssohn and Brahms. Although his administrative duties kept him busy, he completed a handful of large-scale works for choir and orchestra during his first two years. When he took his first cautious steps composing in a newer, less familiar genre, he confided his doubts to his friend Hiller:

“My violin concerto is progressing slowly—I do not feel sure of my feet on this terrain. Do you not think that it is, in fact, very audacious of me to write a violin concerto?”

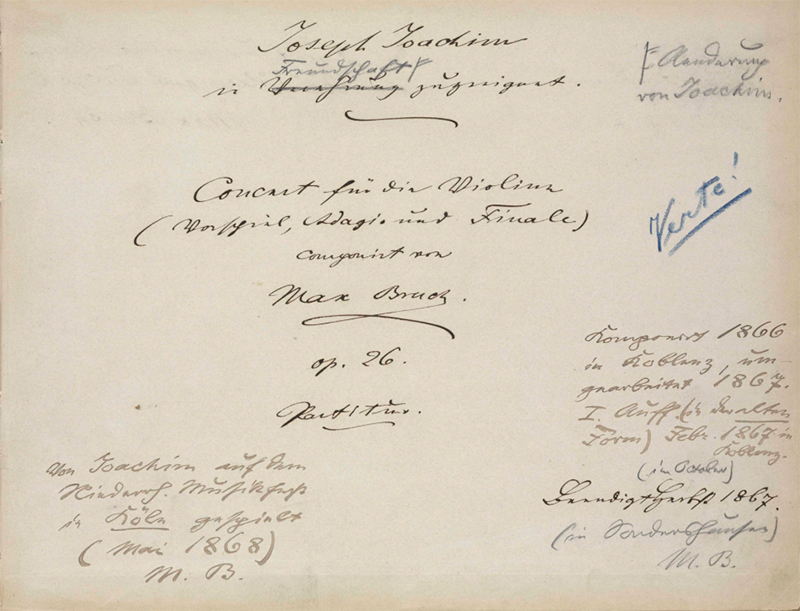

His work on the piece, which would eventually become known as his Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 26, progressed in tentative fits and starts over the course of the next several years. By April 1866 he had completed his first draft, and had it performed. Unhappy with the results, he sent the manuscript to the violinist Joseph Joachim for advice.

Joachim was, in fact, the ideal person to ask for critique, because his authority as an artist was rooted in his direct interaction with the leading composers of the second half of the 19th century. As Clara Schumann had done among pianists, Joachim represented a new type of discipline among violinists, one that made the soloist a servant to the wishes of the composer rather than to self-indulgent, theatrical gestures and splashy technique. However, Joachim was occupied with troubles of his own.

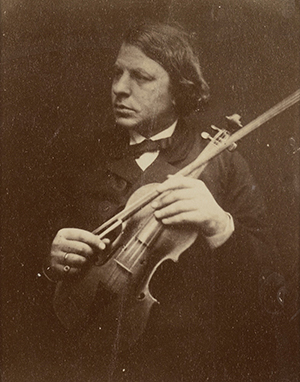

Joseph Joachim

Although he studied in Vienna, Joachim had been thoroughly schooled in the French style of playing. At age 12, his technique fully developed and he began studying in Leipzig with Felix Mendelssohn, who took the boy with him to London to perform Beethoven's Violin Concerto Op. 61, to tremendous public acclaim. Upon Mendelssohn's death, 16-year-old Joachim had then moved to Weimar to further his studies under Franz Liszt. This led to a high-profile career of regular tours in England, Belgium and the Netherlands, as well as to the founding of his professional string quartet—the first ensemble to dedicate entire recitals to the quartet genre. But Joachim’s most visible, most prestigious post was as concertmaster for the Hanover Court.

However, at the point that Joachim received Bruch’s Violin Concerto for perusal, his employer, King George V of Hanover, had just allied himself with Austria against Prussia and was unceremoniously dethroned. Without a royal court to serve, Joachim lost both his income and his status, becoming a private citizen overnight. He packed up his family and moved to Berlin, where he founded the Königliche Hochschule für Musik. It was months before he had time to reply to Bruch.

The Correspondence

The edits that Joachim sent back to Bruch consisted largely of violinistic concerns, adjustments to make the piece fit better under the hand on the fingerboard. But his recommendations regarding the pacing and forward motion of the piece display an astute grasp of musical architecture that only a trained composer would possess. He urged Bruch:

“Finish it very quickly and then allow me, if you do not find my request too forward, to write out a solo part so that I may learn the concerto before we meet, which I hope will be soon.”

Bruch made changes to the piece, which he detailed in a written response to Joachim. As helpful as he found the violinist’s suggestions, he was concerned about how others might perceive them. Many years later, when Joachim’s son was preparing a book of his father’s correspondence, Bruch forbade the publication of this particular letter, writing:

“In this reply I appear dreadfully dependent (not to mention school-boyish) on Joachim…the public would basically believe, when they read all this, that Joachim composed this concerto, and not I. The truth is that I gratefully made use of some of his suggestions, but not others.”

Even after a private performance with the Royal Court Orchestra, conducted by the composer and with Joachim as soloist, Bruch was still not pleased with the work. Another violinist and composer, Ferdinand David, offered advice, but David’s revisions to the solo part were not entirely welcome. Even Bruch’s friend, the conductor Herman Levi, got involved. Levi put Brahms on a pedestal and habitually cited him as the model all other composers should follow, so he felt justified offering Bruch a series of backhanded criticisms, unsolicited:

“Wasn’t I right in my predictions about the violin concerto? I consider the concerto form to be the most difficult, and I warned you.”

And later:

“You should write more violin concertos or sonatas; one cannot work enough on one’s weaknesses.… Do not regret having written the violin concerto; its failure should not overshadow your own convictions.”

Levi stirred up Bruch’s own insecurities to such a point that their friendship chilled. After “nearly half a dozen” revisions the concerto was formally premiered, and Bruch responded to Levi with some saltiness:

“The Concerto gave me the courage to write other instrumental music, even though you believed it was inadequate…it is taking on a wonderful life of its own. Joachim has played in in Bremen, Aachen, Hanover and Brussels, and will play it next in Copenhagen and at the Cologne Music Festival at Pentecost. Auer is playing it on the 17th in Hamburg, Straus in May in London, David in Leipzig, Léonard and Vieuxtemps have ordered it—in short, it is catching on brilliantly.”

The manuscript of the score bears the dedication “Joseph Joachim in Verehrung zugeeignet" (“dedicated in reverence to Joseph Joachim”). The word “Verehrung” (“respect”) was crossed out by Joachim and replaced with “Freundschaft” (“friendship”).

The Violin Concerto, Op. 26

The title of Bruch’s first movement Vorspiel, “prelude,” serves a dual purpose. It defines the first seven minutes of music in terms of its relationship to the Adagio that follows, but it also prepares the audience for its unorthodox structure, curbing expectations of a traditional sonata-form opening. In fact, there is no initial orchestra statement of the theme, just the exchange of musical ideas between orchestra and soloist that call to mind the opening of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto Op. 73 from 75 years previous. The second theme offsets the brilliant opening with a simple folk tune that rises and soars.

The Vorspiel settles seamlessly into the second movement with no break, much as Mendelssohn had done in his Opus 64 Violin Concerto decades earlier. This Adagio is the heart of the work, and it is exemplary of Bruch’s talent for breathtaking simplicity. Like the first movement, the Adagio is trimmed down to its bare essentials: each theme appears only once before Bruch launches into the finale. The Allegro energico has a bounce to it that Brahms seems to echo a decade later in his own violin concerto and its Hungarian flavor seems to be a nod to Joachim’s Magyar roots.

In spite of the emotional honesty of its simpler tunes, the concerto is a virtuoso's dream. Bruch employs open strings, the high register, four-note chords and rapid passages in double stops, all to great effect. The economic length of the piece made it the ideal concerto opener, a sort of amuse bouche to be followed by a more taxing work (and indeed, the ideal length for an LP record side in the 1950s).

Epilogue: American Fraudsters

The bizarre epilogue to the story of the Opus 26 Violin Concerto concerns two charlatans: the sisters Ottilie and Rose Sutro. They were a duo-piano team who first crossed Max Bruch's path in Berlin, where they studied at the Hochschule. When war was declared in 1914, Bruch immediately lost most of his income from royalties on performances: his works were struck from programs because he was German, and when they were performed, there was no means of getting paid. As inflation spiraled, his financial state grew more and more dire, so when the Sutro sisters asked to commission a concerto for two pianos for him, it was a lifeline. He refashioned an unpublished orchestral suite for them into the Concerto for Two Pianos, Op. 88a, under the condition that it be performed only in the U.S.

The sisters premiered the concerto in winter 1916 with Leopold Stokowski and The Philadelphia Orchestra. Neither Rose nor Ottilie Sutro were particularly good pianists, and they proceeded to cut up the concerto, reorchestrate it, restructure it and simplify the piano parts, either because they didn't understand the piece or because their own technique was lacking. As one reviewer in the Public Ledger of Philadelphia observed, "It is not the sort of thing most pianists would choose for a display of their mettle. Their part in it was submerged often, and so it was not easy to tell just what the artistic caliber of the Misses Sutro is." Furthermore, the sisters passed off their cut-and-paste version of the score, comprising more than a thousand of their changes, as an authentic work by Max Bruch. They registered it with the National Library of Congress, but they claimed the copyright for themselves, unbeknownst to Bruch.

Meanwhile, the composer had entrusted the sisters with a second item of much greater value: his manuscript score of the Violin Concerto, Op. 26. When the work had originally premiered, Bruch, on the advice of friends, had sold the printing rights to a German publisher outright, for the minuscule sum of 250 thalers, instead of negotiating for royalties. That publisher had immediately sold the work off to Durand in Paris at a considerable profit. Now, due to the hyperinflation of World War I, Bruch was in desperate financial circumstances. German currency was worthless, and so the Sutro sisters agreed to take Bruch's original score of the violin concerto with them to the U.S. to sell it, and to send the proceeds back to him in American dollars.

But once they returned home, the sisters stonewalled communications from the composer. His son grew skeptical about the matter, but Bruch remained confident, telling him, "My boy, soon I'll be free of all worries when the first dollars arrive." He maintained his good faith until 1920, when he died nearly destitute, still having received no payment from the Sutro sisters and having never again seen the score to his concerto. Several months after his death, the sisters claimed to have sold the manuscript and sent his family the supposed proceeds: a handful of worthless German bills. They refused to divulge any information about the alleged buyer, abruptly cut off all communication and blocked any further enquiries.

Half a century later, it emerged that the sisters had indeed kept the manuscript themselves until 1949, when they quietly sold it to a New York dealer. It is now part of the Mary Flagler Cary Collection of the Pierpont Morgan Library.

Rose and Ottalie Sutro, in a promotional photo from 1917

—Dr. Scot Buzza