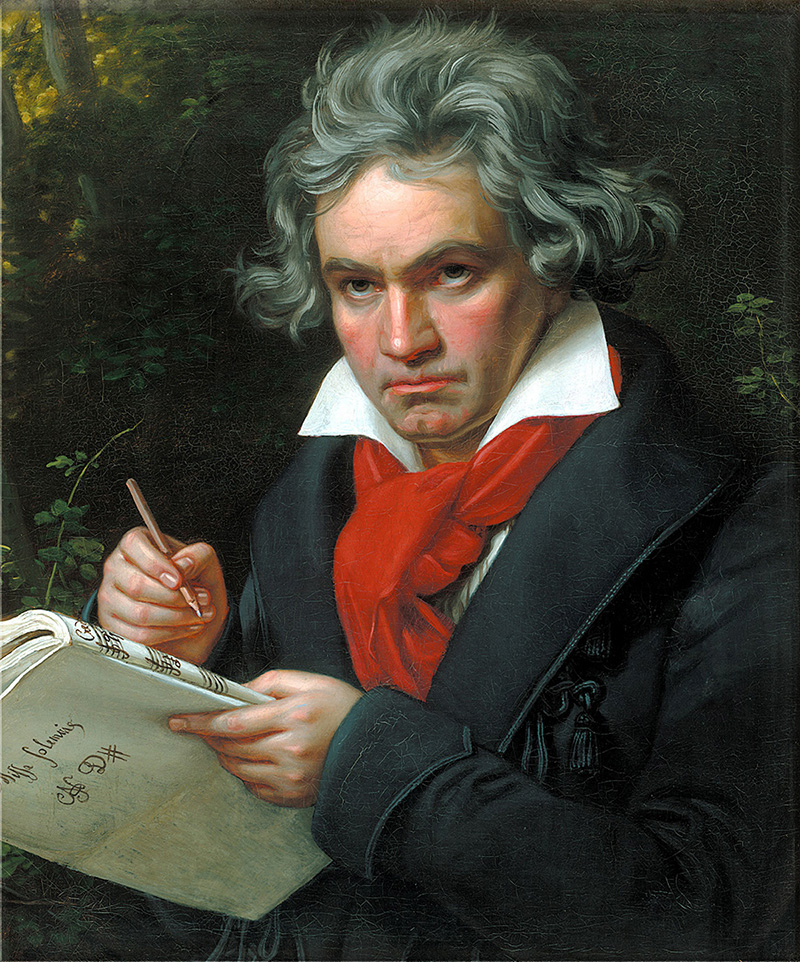

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born: December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria

String Trio in C Minor, Op. 9 No. 3

- Composed: 1797–1798

- Duration: approx. 24 minutes

During his first years after arriving in Vienna in 1792, Beethoven was busy on several fronts. Initial encouragement for the Viennese junket came from the venerable Joseph Haydn, who had heard one of Beethoven’s cantatas on a visit to Bonn earlier in the year and promised to take the young composer as a student if he came to see him. Beethoven, therefore, became a counterpoint pupil of Haydn immediately after his arrival late in 1792, but the two had difficulty getting along — Haydn was too busy, Beethoven was too bullish — and their association soon broke off. Several other teachers followed in short order — Schenk, Albrechtsberger, Förster, Salieri. While Beethoven was busy completing fugal exercises and practicing setting Italian texts for his tutors, he continued to compose, producing works for solo piano, chamber ensembles and wind groups.

It was as a pianist, however, that he gained his first fame among the Viennese. The untamed, passionate, original quality of both his playing and his personality first intrigued and then captivated those who heard him. In catering to the aristocratic audience, Beethoven took on the air of a dandy for a while, dressing in smart clothes, learning to dance (badly), buying a horse and even sporting a powdered wig. That phase of his life did not outlast the 1790s, but in his study of the composer, Peter Latham described Beethoven at the time as “a young giant exulting in his strength and success. Youthful confidence gave him a buoyancy that was both attractive and infectious.”

Among the nobles who served as Beethoven’s patrons after his arrival in Vienna was one Count Johann Georg von Browne-Camus, a descendent of an old Irish family who was at that time fulfilling some ill-defined function in the Habsburg imperial city on behalf of the Empress Catherine II of Russia. Little is known of Browne, but Browne's tutor, Johannes Büel, later an acquaintance of Beethoven, described him as “full of excellent talents and beautiful qualities of heart and spirit on the one hand, and on the other full of weakness and depravity.” He is said to have squandered his fortune, and he ended his days in a public institution.

In the mid-1790s, however, Beethoven received enough generous support from Browne that he dedicated several of his works to him, including the Variations for Cello and Piano on Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen ("Men Who Feel the Call of Love") from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (WoO 46), three Op. 10 piano sonatas, the B-flat Piano Sonata (Op. 22) and three string trios of Op. 9. In appreciation, Browne presented Beethoven with a horse, which the preoccupied composer promptly forgot, thereby allowing his servant to rent out the beast and pocket the profits. The Op. 9 String Trios were apparently composed in 1797 and early 1798. They were popular during the composer’s lifetime and remained so for a considerable time — the records of the “Monday Popular Concerts,” for example, show that the G Major Trio (Op. 9, No. 1) was performed at least 20 times on that London series between 1859 and 1896.

“This is really Beethoven pathos,” wrote the musicologist A.B. Marx (1795–1866) of the C Minor String Trio, “a sustained passion which is built up powerfully and majestically with inevitable logic.” The main theme of the opening movement, a downward thrust through the gapped-note progression that forms the upper half of the minor scale, is presented in a portentous unison by the three participants. A bold figure of hammered chords leads to the contrasting secondary theme, a motive of constricted range accompanied by nervous repeated notes, that passes from violin to viola to cello. Another group of motives allows the tension to subside temporarily as the exposition comes to its end, but the musical drama is quickly rejoined in the development section, based largely on the sudden contrasts and tempestuous rhythms of the main theme. The recapitulation, elided seamlessly to the end of the development, returns the earlier themes in appropriately adjusted tonalities to round out the form of the movement.

The Adagio is an elaborately filigreed essay of deeply introspective expression. Its opening melody, enriched by double stops, is almost suspended in time in its placid rhythmic gait, but, as the melody unfolds, it becomes more animated with extensive decorative figurations. The central section of the movement’s three-part form allows for greater conversational interaction among the instruments. The third movement balances an almost demonic Scherzo with a more brightly hued central trio based on a rising arpeggiated theme. The sonata-form finale opens with a vigorous triplet theme. A more lyrical but still harmonically unsettled melody provides contrast. Both motives are treated in the development, which ends with quiet but dissonant notes in the viola and cello to serve as a bridge to the recapitulation.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda