Gabriel-Urbain Fauré

Born: May 12, 1845, Pamier, Ariège, France

Died: November 4, 1924, Paris, France

Piano Quintet No. 2, Op. 115

- Composed: 1919–1921

- Premiere: May 21, 1921 by Robert Lortat, piano; André Tourret & Victor Gentil, violins; Maurice Vieux, viola; and Gérard Hekking, cello

- Duration: approx. 31 minutes

The Parisian musical world in the late 19th century was a political minefield, polarized between conservative and avant-garde elements and shaped by three distinct forces: the music societies, the conservatories and French music journalism. And though Gabriel Fauré would have preferred invisibility, he ended up as a figurehead for all three: as president of both the conservative nationalist Société nationale de musique and the progressive Société musicale indépendente, as director of the Conservatoire de Paris and as music critic for Le Figaro.

His appointment to the Conservatoire in 1905 had provoked outrage among the most vocal political factions. Not only had he never studied at the Conservatoire himself, but his views on music were notoriously liberal. He enjoyed the esteem of a small group of connoisseurs but, although performances of his works had been fêted in the private salons of the Parisien aristocracy, his music was too modern for the general public, for whom even Wagner was deemed too progressive. During Fauré’s tenure, the reforms he introduced to the academic curriculum were sensible: required courses in music history and harmony, chamber music and large-ensemble training, and a broadened repertoire that extended beyond the war horses of the old masters. He also imposed personnel policies, to avoid professional conflicts of interest and diffuse undercurrents of favoritism. Yet, the daily battles with colleagues had become tiresome, and he grew to resent the distraction from his composing.

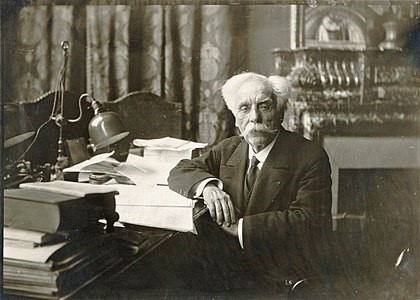

By 1919, after running the institution for 14 years, Fauré was exhausted. His health had become poor due to a lifetime of heavy smoking, and, moreover, he was suffering a peculiar kind of hearing loss that distorted pitches in the extreme low and high ranges. When political tides turned and the government requested his resignation from the Conservatoire, he felt a sense of relief. He withdrew to spend the summer with his mistress, Marguerite Hasselmans, in Annecy-le-Vieux in a large and peaceful country house overlooking the valley and the lake beyond, from which he wrote to his wife, Marie, “I should bless the destiny which has relieved me of such a heavy burden…. I cannot say enough how I savor the idea of my deliverance!”

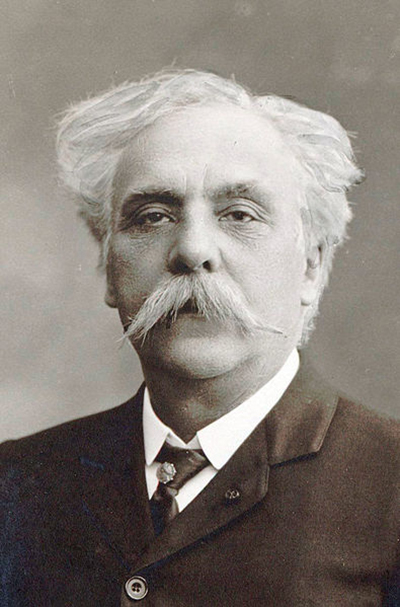

Gabriel Fauré as director of the Conservatoire de Paris

In September of that year, living back in Paris and recharged with a new surge of creativity, he was finally free to compose, uninterrupted. The result was a handful of chamber works that would eventually crown his career: the second cello sonata, the song cycle L’horizon chimérique, the piano trio, the string quartet and his Piano Quintet No. 2, Op. 115.

Fauré’s Quintet was premiered on May 21, 1921, at the Conservatoire, presented by the Société nationale de musique. The composer’s friend Robert Lortat was the pianist, and prominent faculty filled out the ensemble: André Tourret and Victor Gentil played violin, Maurice Vieux was the violist and Gérard Hekking the cellist. Fauré’s son Philippe described the event:

When [the Quintet] was played for the first time in the Old Hall of the Conservatoire by artists at their peak, tremendously moved, the public from the first pages was immediately carried away, surprised and dazzled. They had expected a masterwork, but not this! They had known that Gabriel Fauré would aim high, but they had not believed he would reach such a summit!… At the final chord, everyone stood up. They shouted out, hands stretched toward the grand loge where Gabriel Fauré was hidden, himself having heard nothing at all.

Critics saw in Fauré’s Quintet the embodiment of youth and serenity. Émile Vuillermoz wrote in Le Temps:

It has the youthful privilege of freshness, ardor, generosity and persuasive tenderness; it also possesses the sober gifts of wisdom, idealized passion, fine and delectable balance, and tranquil reason.

Fauré composed the first movement of the Quintet after completing the middle movements, as was his habit. In it, the absence of low bass pitches from the piano part is conspicuous—perhaps related to the deficits in the composer’s hearing? The opening viola melody suggests an ambiguous meter before finally settling into triple time. It then telescopes out into a single line that extends unbroken to the end of the movement. Lyric and simple on the surface, its underlying form is deceptively complex; it develops continuously over four distinct sections, climaxing in a restatement of the opening theme.

The second movement is a particularly French version of the scherzo—not the heavy-footed dance found in the works of German composers, but a more ephemeral, fleeting ditty, tossed off effortlessly and punctuated with bursts of pizzicato. Fauré had first introduced this variant of the genre decades earlier in his Violin Sonata, Op. 13, and it became the prototype for the scherzo movements in the string quartets of both Debussy and Ravel.

The following Andante moderato replaces that kinetic energy with a sense of reminiscence that borders on melancholy. The composer introduces the theme in G major in the strings and then offsets it with a new tune in the piano. The strings and piano together develop those melodic ideas through several remote keys before settling back into G major again.

With the final movement, Fauré breaks the symmetry of the classical rondo by means of an unassuming theme that progressively becomes prominent and finally dominates, leading to a great crescendo that brings the movement and the entire work to a climax in C major.

Throughout his entire oeuvre, Fauré had successfully sidestepped one of the pitfalls common in the piano chamber works of many great composers such as Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms: he never reduced the strings to the role of a miniature orchestra, secondary in importance to the piano, and never treated the pianist as principal soloist. Instead, he allowed each instrumentalist autonomy to interact with the others on their own terms.

The year Gabriele Fauré was born, Liszt was at the peak of his popularity in Paris; the year he died Wozzeck premiered. Thus, he represents a particular link in the evolution of French music of the 19th and 20th centuries. Although he himself was the face and voice of such quintessential Parisian establishments as Le Figaro, the Societées, and the Conservatoire, Fauré's musical idiom represented no ideals other than his own. The result was a new, distinctly French type of poetry in music with its own vocabulary and syntax, one that broke away from the influence of German Romanticism in its transparency, elasticity and volatility, as well as in its unrestrained honesty.

—Dr. Scot Buzza