Visionaries in Sound and Motion

April 12, 2024

Flagstaff Symphony Orchestra

with Shrine of the Ages and Master Chorale of Flagstaff

Mary D. Watkins, Five Movements in Color

Charles Latshaw, conductor

1. Once Upon a Time

2. Soul of Remembrance

3. Urban Suave

4. Slow Burn

5. Drive by Runner

Program Notes (adapted from John P. Varineau)

Mary Watkins wrote Five Movements in Color on commission from the Camellia Orchestra in Sacramento, California. Intended to be part of Black History Month, she called the work “a statement about the African-American experience.” She describes the first movement, “Once Upon a Time,” as beginning with “African drums, then the strings begin to tell a story that moves from peaceful to active to violent.” A melody floats over a march in “Soul of Remembrance” (the second movement), what Watkins calls “my historical piece about enslaved Africans struggling to understand their new lives in the U.S. and starting their long march to be recognized as fully human.”

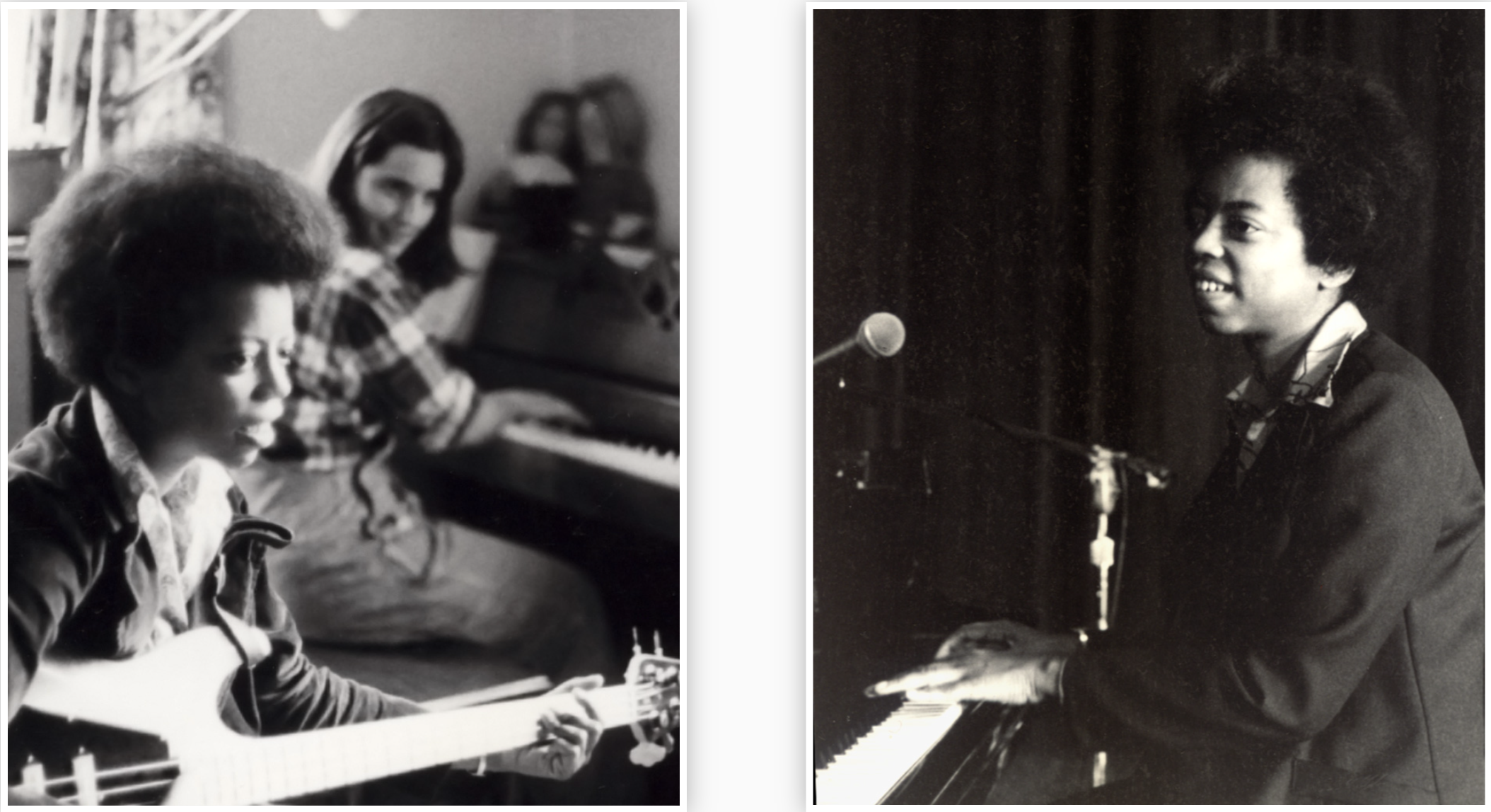

About the Composer

Mary D. Watkins is an eclectic composer and pianist of the classical and jazz traditions, often incorporating one with the other or bringing the various styles of ethnic, blues, gospel, country, folk, and pop music into her original works. Her versatility as a composer, arranger, pianist, and producer has led her to compose for symphony orchestra, chamber and jazz ensembles, film, and theatre. In 1972 she received a bachelor’s degree in Music Composition from Howard University in Washington, D.C. She later earned her living performing with jazz groups in the DC area and as Musical Director, Resident Composer and pianist for theatre and modern dance groups.

Intermission - 15 minutes

Jocelyn Hagen, The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci

with Shrine of the Ages and Master Chorale of Flagstaff

Tim Westerhaus, conductor

Jacob LaBate, Muséik Projections Operator

- Painting and Drawing

2. Practice

3. Ripples

4. The Greatest Good

5. Vitruvian Man

6. Invention (orchestra only)

7. Nature

8. Perception

9. Look at the Stars

Program Notes (by Jocelyn Hagen)

Rivers of ink have been dedicated to the study of the life and work of Leonardo da Vinci. His genius has been articulated by scholars, historians, artists, engineers, and scientists for centuries, and the legacy of his work will continue to endure the test of time because of his remarkable synthesis of art, science and design. When I first began researching da Vinci and his notebooks, I was overwhelmed. How was I to condense this huge body of work into one 35 minute symphony? (Over 5,000 pages of manuscript have been found.) There was no way I could include the entirety of this work, so my goal became serving the spirit of his work and his curious mind.

One of the biggest lessons I gleaned from studying his work was the importance of being willing to fail. He was a man known as much for his failures as his successes, and this did not dampen his creativity or his drive. More than anything he just wanted to understand the world around him, and he didn’t let his pride or ego stand in the way of posing the tough questions or trying to answer them. he remained open to the possibility of new discoveries and allowed himself the freedom to change his mind. You can see this this attribute of his personality beautifully in the opening of the symphony, when his handwriting is scrolling across the screen. He very quickly crosses out a word, pauses, then continues on with his idea.

Mistakes and practice were a big part of his creative process, as they should be. And did you know he wrote right to left, backwards, as if in a mirror? Leonardo da Vinci did not invent the Vitruvian man, but it is without doubt the most recognizable image from all his notebook pages. Vitruvius, the architect, described the human figure as being the principal source of proportion among the classical orders of architecture. Da Vinci was one of several artists who examined this theory by sketching a “Vitruvian man.” The infamous image demonstrates the blend of mathematics and art as well as da Vinci’s deep understanding of proportion. In the fifth movement you will hear the choir sing the different ideal proportions of the human body and see an overlay of his incredibly detailed (and accurate!) sketches of the human form on top of a live model: dancer Stephen Schroeder.

And who could forget da Vinci’s famous flying machines? In truth he invented several gliders in his lifetime, and had a preliminary understanding of aerodynamics, which he called “the science of the winds,” centuries ahead of George Cayley (credited with the discovery of aerodynamics in 1809). He invented automatons, weapons of war, and many other inventions as well. The little machines come to life in beautiful animations on the screen, and I invented my own little musical machines to accompany them. They whir and spin in their own time, creating a fantastic soundtrack to the lively imagery in the sixth movement.

“Wisdom is the daughter of experience” is one of the most famous quotes from da Vinci’s notebooks. It seemed only fitting that this line end the work, complete with images of the night sky and his beautiful portrait of an old man (rumored to be himself).

About the Composer

Jocelyn Hagen composes music that has been described as “simply magical” (Fanfare Magazine) and “dramatic and deeply moving” (Star Tribune, Minneapolis/St. Paul). She is a pioneer in the field of composition, pushing the expectations of musicians and audiences with large-scale multimedia works, electro-acoustic music, dance, opera, and publishing. Her first forays into composition were via songwriting, still very evident in her work. Most of her compositions are for the voice: solo, chamber and choral. Her melodic music is rhythmically driven and texturally complex, rich in color and deeply heartfelt.