Piano Trio (World Premiere)

Composer: Sheridan Seyfried

III. Slow

IV. Fast

Piano Trio No. 2 in e minor, Op. 67

Composer: Dmitri Shostakovich

- Andante

- Allegro con brio

- Largo

- Allegretto

Intermission

Piano Trio No. 4 in e minor, Op. 90, B. 166, “Dumky”

Composer: Antonín Dvořák

- Lento maestoso — Allegro quasi doppio movimento

- Poco adagio — Vivace non troppo — Vivace

- Andante — Vivace non troppo — Allegretto

- Andante moderato — Allegretto scherzando — Quasi tempo di marcia

- Allegro

- Lento maestoso

Piano Trio (World Premiere)

Composer: Sheridan Seyfried

Today, you’ll be hearing the final two movements (a slow movement and a spirited finale) from a longer work I’m currently writing for Dennis, Jonah and Sean. In composing, I believe that inspiration can be taken from existing works by others (either consciously or unconsciously) so long as the end product meets a high artistic standard. In the case of each of these movements, I consciously drew upon material from music I love.

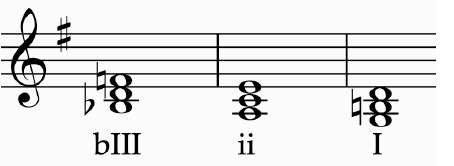

In the case of the third movement, my starting point was a popular song from the 90s—my youth (music from one’s adolescence holds special emotional resonance.) The song “Hey Now!”, by the British rock act Oasis, contains a closing chord progression with unusual features: a chord which would normally be minor is flatted (lowered) and made major (a device borrowed from the blues, giving us the “flat three” chord), and a chord which normally goes elsewhere (“two” usually goes to “five”) instead resolves with folk-like directness (it goes to “one” without first going to “five”):

To tie this unusual progression together, the Oasis melody emphasizes one note, “g”, over all of these chords. In my own composition, I changed the melody itself (naturally), but kept what I viewed as its characteristic features—the chords themselves and the melody’s fixation on “g”. Working backwards from there, I composed a 16-bar melody that naturally led to this place. In the finished movement, the juxtaposition of jazz-influenced chords alongside more simple, folk-like harmonies, is all inherent in the DNA of this three-chord progression.

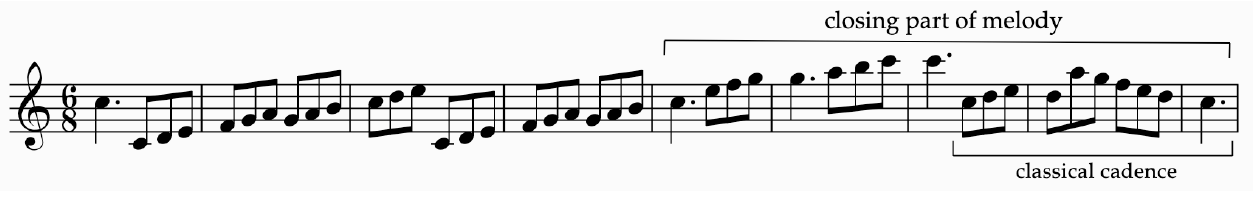

In the finale of my composition, the starting point was the high-energy final movement of Mozart’s 34th Symphony. I’ve learned from Beethoven’s music that beginning melodies with phrases that might more customarily end them is a fruitful creative procedure. The “closing part” of Mozart’s melody seemed as if it deserved to be the beginning of a melody of its own (the part marked “classical cadence” I altered since it was too conclusive—and stylistically classical—for its new context):

I structured my movement in “rondo” form—a form characterized by the frequent recurrence of a particular melody (and one well suited to closing movements; high spirits are more important than sophistication). All the melodic ideas in the movement originate from this one basic source—a procedure more typical of Haydn than Mozart. (The latter liked instead to write strongly contrasting melodies.) The work concludes with an exuberant coda.

Dmitri Shostakovich

Piano Trio No. 2 in e minor, Op. 67

Despite his prodigious cycle of 15 string quartets, Shostakovich wrote sparingly for other chamber music ensembles: a cello sonata, violin sonata, piano quintet and two piano trios. His first piano trio was a single movement composition from 1923 written when Shostakovich was only 17. A student work, it is far out shadowed by the mature second piano trio, a substantial four-movement work offering the full range of Shostakovich's artistry and emotional intensity particularly as expressed so intimately in his "private" chamber music. In a kind of tradition following Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov, Shostakovich created an elegiac trio in memory of his close friend Ivan Sollertinsky, a brilliant musicologist and critic who died suddenly of a heart attack while still a relatively young man. Written in the summer of 1944 in the midst of WWII, the trio, like many of Shostakovich's works, seems to comment more broadly on the tenor of the times suggesting an elegy for the tragic victims of war in general.

The trio begins very quietly in eerie high harmonics as a solo cello introduces a meditative subject in its highest range that grows, when joined by violin and piano into a weighty fugue, a prominent feature of other Shostakovich chamber works including the eighth quartet and the piano quintet. As in all three works, the fugue is deeply tinged with melancholy. Portions of the fugue subject transform into new thematic materials across of the movement of generally escalating motion and dynamics.

The brisk and spiky scherzo is unmistakably Shostakovich. It constantly teeters on the edge between lively and frantic, between rolling scales and harsh, repetitive rhythmic motifs like a jovial folk dance where escalating mirth swerves dizzily towards obsessive mania. The virtuosity seems to boil and effervesce into pizzicato bubbles as a brilliant string duo trades figure and ground with the piano.

The slow, third movement is a deeply-felt lament, a passionate funeral dirge that grows out of an initial stark chord progression from the piano laid like a grave stone to serve as a ground base in a chaconne form. The finale breaks the grief with a compelling musical narrative featuring a march, piquant folk dancing and a poignant, weeping recall of fugal subject from the first movement as the music becomes a literal manifestation of elegiac recall, a rushing memory of what has past and gone. Composer and critic Arthur Cohn notes in his typically terse but sharply perceptive style that here Shostakovich pictures "the horrible forced dance of Jews before they were machine-gunned to death." Whether the loss of a close friend or of a whole nation in the midst of a world war, the tragedy had a deep impact on Shostakovich: prefigured in the first movement, the sharply etched finale theme resurfaces yet again in the monumental personal testimony of the eighth quartet.

© Kai Christiansen Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

Piano Trio in E Minor, Op. 90 Dumky (1890-91)

Dvořák wrote reams of incredible chamber music in all forms. His combination of natural lyricism, clear texture, vivid color, rhythmic vitality and a sure sense of dramatic development place him among the composer gods with a noticeable affinity for Schubert who was undoubtedly a strong influence. After the "American" Quartet, The "Dumky" Trio is probably Dvořák’s most celebrated chamber work, neck and neck with the Piano Quintet in A major. If the American quartet is a possible mirror of indigenous American folk music, the Dumky Trio is pure Bohemian and Czech, an even more convincing reflection of a national folk tradition, this time, in Dvořák’s own mother tongue. He composed the Dumky, his fourth and final piano trio, in 1891 at the age of 50, just prior to his legendary trip to the America.

The word dumky is the plural for dumka, a Czech and Ukrainian term that, in summary, means "ballad", “elegy” or “lament.” A dumka was a kind of poetic ballad or tribute, often told about a heroic saga, a tragic historical event or the plea of a subjugated people. It fostered a musical genre of single-movement pieces that mix slow somber melancholy with fast, wild, exuberance almost like two stages of grief. Dvořák wrote a number of dumky scattered throughout his work and each one is a showcase of passionate Czech folk music in a sort of idealized classical realization. The Dumky Trio is essentially a suite of six dumky, each of the six movements a complete dumka exhibiting a dichotomy of low and fast, dour and bright, with masterful contrast of character, rhythm, tempo and color. Since the first three dumky are played in sequence, without pause, some have commented that the Dumky Trio coalesces into a kind of classical three or four-movement design. A nearly unbroken tapestry of sectional contrasts spans the movements making for a compelling, continuous narrative. The fourth movement reverses the dichotomy by starting out fast and lively rather than slow and deep and the last dumka is perfectly placed as the finale. It seems certain that Dvořák arranged and possibly composed the suite with a layered conception of flow, unity and dramatic shape as a series of heroic tales and epic laments, a book of fairytales, a suite of songs in a prevailing national style, each singular, exotic species in a common thread. Dvořák wrote other such collections such as his breakthrough Slavonic Dances and the set of string quartet “songs” knows as The "Cypresses".

Dvořák was a master of color in all of his music, whether written for a full orchestral palette or, nearly the opposite, a string quartet. But his chamber music with piano is a particularly rich vein of color. With Dvořák, the very term “color” becomes slippery and ambiguous. The constantly changing sonorities in his music involve instrumental techniques and carefully chosen ensemble configurations, but the color seems likewise inseparable from the essential elements of the music more fundamental than this: the melody and rhythm. All these elements are melded together creating vivid expressions and impressions in what is the brilliant signature style of Dvořák himself. But witness here how masterfully he deploys the piano trio discovering ranges of sonic expression hitherto unknown (expect perhaps to Schubert).

The clear, earthy, emotionally full and broadly accessible aspects of Dvořák’s most famous music span his entire career. The American Quartet often serves as the poster child of this lovely trend in Dvořák’s music and therefore it may often become entangled with a notion that it was unique to his American works or to a specific quest for a folk music inspiration in the new world. But the "Dumky" Trio and the Terzetto for 2 violins and viola of a few years prior both pre-date Dvořák’s American sojourn and yet they exhibit many of the same qualities including the spare, open harmonies, rustic rhythms and pentatonic folk scales. One might say that one set of works has a slight Bohemian accent, the other that of the American Midwest, both sharing underlying traits of world folk traditions. But really what they share is Dvořák’s own innate musical personality a proclivity for direct and bountiful expression with robust, passionate vitality from a generous and gifted sensibility.

© Kai Christiansen Used by permission. All rights reserved.