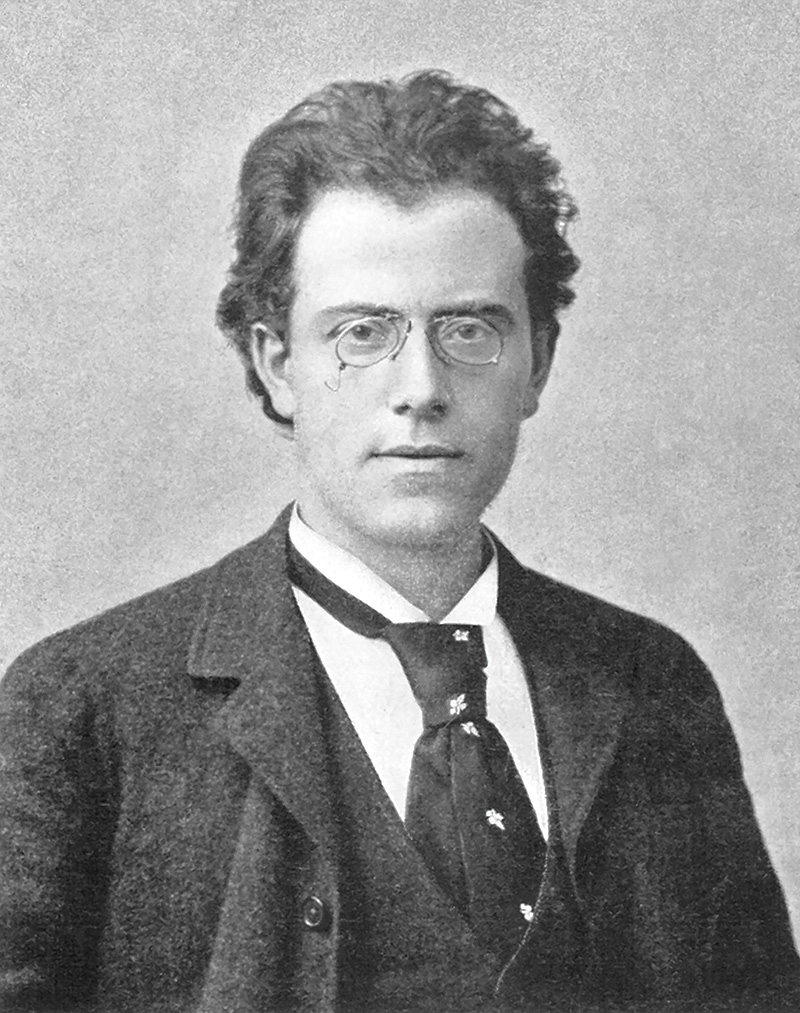

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7, 1860, Kalist, Bohemia

Died: May 18, 1911, Vienna, Austria

Symphony No. 4 in G Major

- Composed: 1899–1900

- Premiere: November 11, 1901 in Munich, conducted by the composer

- Instrumentation: soprano solo, 4 flutes (incl. 2 piccolos), 3 oboes (incl. English horn), 3 clarinets, (incl. E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet), 3 bassoons (incl. contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, sleigh bells, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, harp, string

- CSO Notable Performances: First: March 1926, Fritz Reiner conducting. Most Recent: November 2021, James Gaffigan conducting

- Duration: approx. 54 minutes

Mahler’s Symphony No. 4, the most modest in length and orchestral requirements of his 10, had its roots as far back as 1892, when the composer was 32. Those were the years, extending through the composition of the Fourth Symphony, during which Mahler was imbibing the folk traditions of Germany as they were set down in an early-19th-century anthology of poems titled Des Knaben Wunderhorn (“The Youth’s Magic Horn”). American musicologist Edward Downes noted a deep-seated personal need in Mahler’s interest in these simple peasant verses: “Like most German Romantic artists, Mahler felt a love for folk art amounting almost to worship. In part this may have been the nostalgia of the complex intellectual city-dweller for an Eden of lost innocence, of freshness, of naïveté.” That vein of innocence, of child-like simplicity, is at the heart of Mahler’s lovely Fourth Symphony.

In 1892, Mahler set to music one of the Wunderhorn poems, Der Himmel hängt voll Geigen (“Heaven is chock full of violins”). He completed the song, which he named after its first line, Wir geniessen die himmlischen Freuden (“We revel in heavenly pleasures”), in February 1892 and made an orchestral arrangement for it the following month. When he set to work on his Third Symphony in 1895, he intended to include this song as the last of its movements. The vast musical panorama of the Third Symphony, perhaps the best example of Mahler’s philosophy that sought to embody “the world in a symphony,” was conceived to address individual movements to such matters as “What the flowers tell me,” “What the forest creatures tell me” and so forth for “the night,” “the angels” and “love.” The finale was to have included Wir geniessen die himmlischen Freuden to elucidate “What the child tells me.” Mahler, however, decided to drop that song from the Third Symphony, probably because it would have been an anti-climax after the stentorian ending of the preceding movement. Instead, he determined to explore the world of this “child of heaven” more extensively in a separate work. Thus was the Fourth Symphony born.

It is important to understanding the Fourth Symphony to realize that its entire mood and structure are built to lead to the finale — the first three movements serve to prepare for and illuminate the closing vision of Wir geniessen die himmlischen Freuden. The composer is reported to have said, “In the first three movements there reigns the serenity of a higher realm, a realm strange to us, oddly frightening, even terrifying. In the finale, the child, which in its previous existence belonged to this higher realm, tells us what it all means….” The Symphony opens with the distinctive sound of sleigh bells that recurs at important structural points throughout the movement. A number of melodic ideas comprise the main theme group before the music moves to the second theme, a sweet, Viennese melody high in the cellos. The sleigh bells mark the beginning of a lengthy development section that explores much of the material heard thus far, with a particular emphasis on the clear pipings of the augmented woodwind choir. After one of the few large climaxes of the symphony, the development quiets before it comes to an abrupt stop. The music takes a quick breath, and the recapitulation begins in the sunny mood of the opening. The exposition themes are again assayed to bring the movement to an invigorating close.

Mahler’s original designation for the second-movement scherzo was Freund Hein spielt auf (“Friend Hein plays”). “Hein” was the character of German legend who used his fiddle to lure reluctant travelers to the Great Beyond. This eerie movement, perhaps inspired by the not dissimilar visions of Liszt, Saint-Saëns and Berlioz, alternates a diabolical scherzo with brighter trios. Much of the mood comes from the solo violinist, who is instructed to tune a second instrument a full step higher than normal to produce a more strident tone quality. Of this movement, Mahler wrote, “The scherzo is so uncanny, almost sinister, that your hair may stand on end. Yet in the following Adagio, where all complications are dissolved, you will feel that it was not really all that sinister….” Rather like a bad dream followed by a reassuring sunrise.

The serene third movement is in the form of a variation on two themes, though it follows the formal outlines of each theme only tenuously. The first set of variations, dominated by the string choir founded upon a resonant pizzicato bass line, alternates with the second set of variations, given largely to the winds. The oboe introduces the second theme.

The vision of the closing movement is couched in the simplest of musical forms — the strophic song. Each verse of the text, filled with images of an idealized Medieval peasant life, ends with a chorale-like refrain borrowed from the music of the alto solo in the Third Symphony. The sleigh bells and accompanying music of the first movement return (the noted English musicologist Sir Donald Tovey dubbed these, rather ingloriously, “farm-yard noises”) to mark the beginnings of further stanzas. For the concluding stanza, Mahler executed a harmonic sleight-of-hand as the music floats upward from its G major base to the airy key of E major. More than just a technical device, this gesture gives a special meaning to the closing text, “There’s no music at all on earth, which can ever compare with ours,” sung by the heaven-blessed child. Its beauty, calm and simplicity are among the most pacific moments in all of music.

—©Dr. Richard E. Rodda