- Born December 24, 1863, in Madrid

- Died June 2, 1939, in San Sebastián, Spain

- Composed c. 1886

- Duration: 18 minutes

Enrique Fernández Arbós began his professional life studying violin in his hometown of Madrid, before moving to Brussels to work with Henri Vieuxtemps and to study composition with François-Auguste Gevaert. While in Belgium, he began to play piano trios with fellow students, including the Spanish cellist Agustín Rubio. The violinist and cellist eventually swapped out their pianist for Isaac Albéniz, who, like Arbós, studied composition with Gevaert. The three toured widely together in the 1880s as the Iberian Trio, and Arbós and Albéniz remained close friends and colleagues when they both moved to London in the early 1890s.

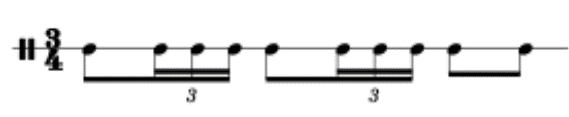

Several of the compositions that Arbós completed and published in his lifetime were for piano trio, including the 1886 Three Original Pieces in Spanish Style, his Op. 1. Each movement is modeled on a different Spanish dance. The first, Bolero, is in a form from the late 18th century. Though the dance itself faded in popularity over the course of the 19th century, many composers of the Romantic era, including Frédéric Chopin, Clara Schumann, Camille Saint-Saëns, and even Giuseppe Verdi, wrote music based on the prevailing rhythmic idea of the bolero. The dance is in a moderately paced 3/4 time, but it features a hook that gives it a distinctive, playful quality: between the first two beats, there is always a flourish that emphasizes the weight of the second pulse of the measure. In perhaps the most famous bolero, that written in 1928 by Maurice Ravel, each of the first two beats is followed by snare drum triplets, which serve this purpose.

In the first movement of Arbós’s Tres piezas, a similar triplet rhythm sometimes occurs in the strings, mixed in with a bouncing pizzicato accompaniment line that supports the piano’s version of the melody. But the piece is dominated by other variations on the idea of placing the second beat with a little lift, including a quick rising arpeggiated figure in the keyboard, and urgent dotted figures on a fixed note that lead to a deliberate accent on the second beat.

The second piece in Arbós’s set is a habanera, the slow and seductive dance made famous by Georges Bizet’s Carmen. A habanera always features a prevailing, march-like rhythm: a dotted figure, plus two even notes. But above, the melody floats and plays with the tempo, forming a strong counterpoint with the stately bassline. In his movement, Arbós has all these usual elements, and he mixes in triplet passages that further destabilize the pulse. He also writes out the stately dotted gesture in different ways, suggesting improvised performance inflections. At the end of the dance, he artfully blends the dotted figures and triplets, decomposing the basic stuff of a habanera and re-synthesizing it into something quite sublime.

The finale of this trio, Seguidillas Gitanas, is an inflection of an Andalusian dance inspired by the Roma community based in Granada. A seguidilla, like a bolero, is in 3/4 time, and includes a lift before the second beat of the measure. But it is in a quick tempo, and generally positive in mood. Phrases often start on an empty beat, so the prevailing feeling is one of constant forward drive. Arbós links this movement together with the opening Bolero in different ways. The dance of the bolero evolved as a variant of the seguidilla, and here Arbós artfully turns this historical relationship into a source of organic continuity, lending the whole work a remarkable degree of coherence.