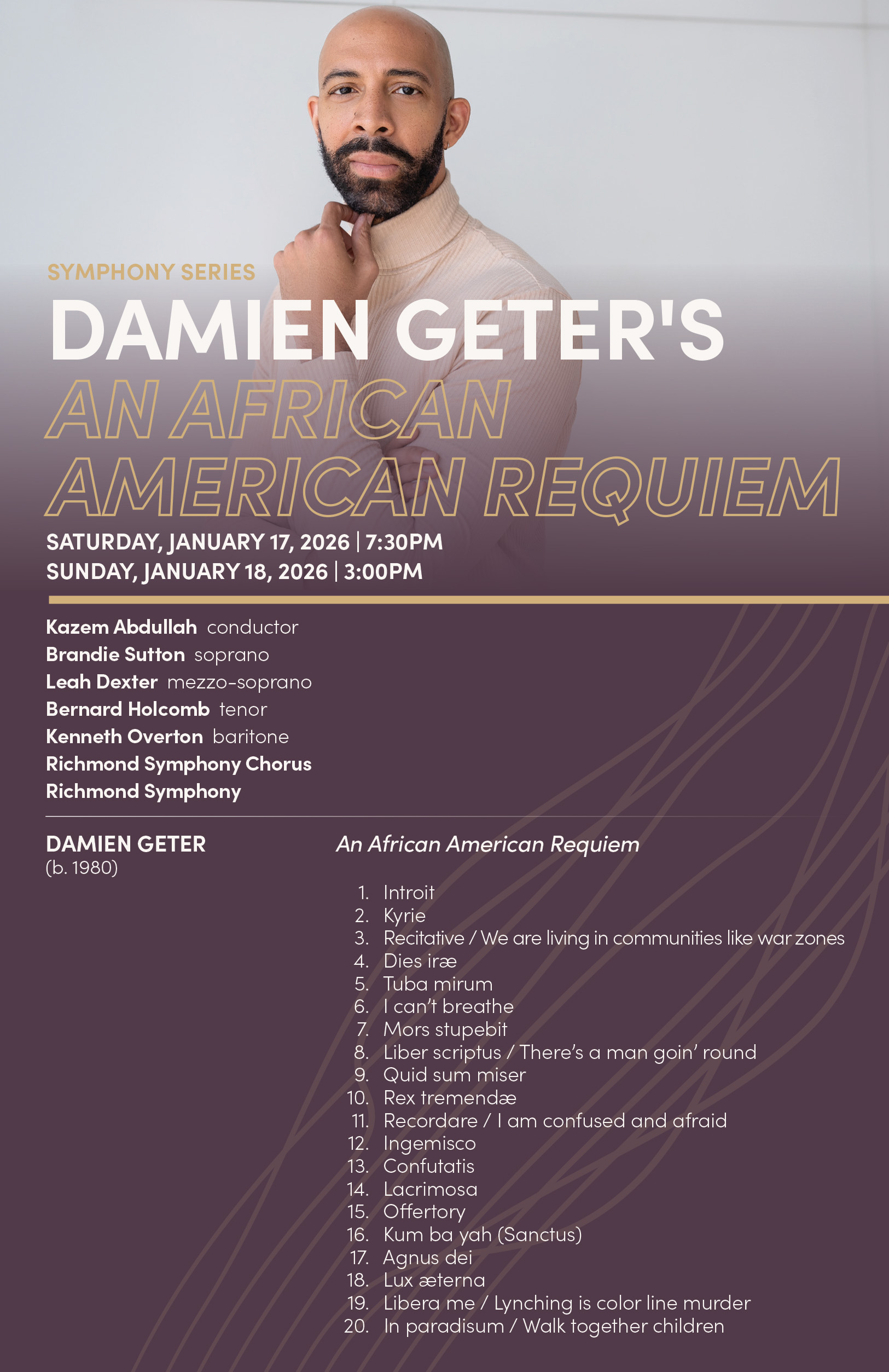

DAMIEN GETER

An African American Requiem

SATURDAY, January 17, 2026 | 7:30PM

SUNDAY, January 18, 2026 | 3:00PM

Kazem Abdullah | conductor

Brandie Sutton | soprano

Leah Dexter | mezzo-soprano

Bernard Holcomb | tenor

Kenneth Overton | baritone

RICHMOND SYMPHONY CHORUS

80 minutes

Damien Geter’s role as Composer-in-Residence with the Richmond Symphony has been about more than presenting his music in performance. It has meant cultivating relationships—with musicians, audiences, and the community—to explore how music can speak to the American experience in real time. Over the course of his tenure, Geter has curated programs, mentored young artists, and composed works that reflect both personal history and national reckoning.

Currently based in Chicago, Geter was born in Petersburg and raised in Chesterfield County and studied piano and organ as a child before focusing on trumpet at Old Dominion University. “Many of my earliest musical memories,” he recalls, “came from sitting in the Richmond Symphony concert hall as a young person.”

Within this context, An African American Requiem takes on special resonance as the most ambitious realization of his partnership with the Symphony. As Music Director Valentina Peleggi observes, “This is the first official concert in 2026, when we mark the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. We wanted to present a piece that speaks about the concept of America nowadays. After three years with Damien as our composer-in-residence, we felt this was exactly the moment to perform such a masterpiece.”

An African American Requiem is a sweeping, concert-length score for orchestra, chorus, and soloists. Geter has dedicated it “to the victims of racial violence,” shaping the work as a memorial to lives tragically lost.

The idea for An African American Requiem was sparked early in 2017, at a moment of national tension and transition. Geter had already been sketching ideas in 2016, in response to the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and other Black Americans whose deaths at the hands of police or vigilantes had become symbols of racial injustice. He resolved to create a full-scale Requiem. At the time, Geter was a member of Portland’s Resonance Ensemble, where Artistic Director Katherine FitzGibbon recognized the urgency of his vision and commissioned the work.

The premiere, postponed by the pandemic, finally took place in May 2022 with Resonance and the Oregon Symphony, followed by a performance at the Kennedy Center. It has already begun to establish itself as one of the most significant large-scale choral statements of recent years.

A Requiem traditionally sets the Roman Catholic Mass for the Dead, honoring the departed and offering prayers on their behalf. Geter looked to Verdi’s Requiem as his principal model. At the same time, Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, which premiered in 1962, offered an inspiring precedent for how the ancient ritual could be transformed into commentary on urgent contemporary realities. Like Britten, Geter interweaves the Latin liturgy with other voices—in his case, voices drawn from African American experience, the work of activists, and spiritual song.

The opening Introit follows Verdi’s precedent, and his vividly dramatic setting of the Dies irae (“Day of Wrath”) also finds echoes in Geter’s treatment, including the emphatic role of brass. But Geter extends the form across twenty movements, introducing the contemporary angle already in the third movement, between the Kyrie and the Dies irae, when the soprano soloist sings words by Sacramento activist Jamilia Land: “We are living in communities that are like war zones.”

Later, amid the sequence of texts that comprise the Dies irae—which originated as a rhymed medieval hymn depicting what awaits humanity at the Last Judgment—a tenor sings Eric Garner’s last words, “I can’t breathe,” just before the chorus launches the terrifying vision of Mors stupebit.

Elsewhere, Geter embeds familiar national symbols in unsettling ways. In the Lacrimosa, a solo clarinet plays a haunting minor-key version of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” leaving silent the climactic note where the word “free” would occur. He also turns to Ida B. Wells, the pioneering Black journalist and civil-rights leader, setting her 1909 speech “Lynching is Color-Line Murder” before the section In paradisum, which envisions the angels leading the departed into Paradise.

Spirituals such as “There’s a Man Goin’ Round Taking Names” and “Kum Ba Yah” are folded into the stylistic collage of Geter’s wide-ranging score. “There’s jazz, especially in the Ida B. Wells movement,” he notes. “But overall, this is a straight-up piece of classical music that interweaves all types of music.”

The stylistic breadth allows Geter to move between emotional extremes. “The music tells the story just as much as the words,” Geter explains. “I’m driven by text. The music supports the text, and the text highlights the music. Even when I’m writing pieces that have no text, I still think about the drama.” An African American Requiem shifts between moments of despair and flashes of hope. “The ending in B major sounds triumphant, in a way,” he says, “but to me this is a dark key.”

Asked about the message he intends to convey, Geter responds: “I’m not sure I have a message per se. What I’m trying to do is to honor and commemorate those who have perished because of racism. The music is the message.”

(c)2025 Thomas May

SUNG TEXT: There’s A Man Goin’ Round/Liber Scriptus Recordare Ingemisco Lacrimosa Agnus Dei | Translation: The day of wrath, that day The trumpet, scattering a wondrous sound through The written book will be brought forth, Remember, merciful Jesus, Seeking me, though faint and weary, Once the cursed have been silenced, Tearful will be that day, Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the |

(Libera Me) Lynching is Color-Line Murder 5

The lynching record for a quarter of a century merits the thoughtful study of the American people.

It presents three salient facts:

First, lynching is color-line murder.

Second, crimes against women is the excuse, not the cause.

Third, it is a national crime and requires a national remedy. (Continued on the following page)

5. By Ida B. Wells (Edited).

(Libera Me) (cont’d) This was wholly political, its purpose being to suppress the colored vote by intimidation and murder… the purpose was accomplished, and the Black vote was suppressed. But mob murder continued. From 1882, in which year 52 were lynched, down to the present, lynching has been along the color line. Mob murder increased yearly until in 1892; more than 200 victims were lynched and statistics show that 3,284 men, women and children have been put to death in this quarter of a century. (Twenty-eight human beings burned at the stake, one of them a woman and two of them children,) the awful indictment against American civilization – (the gruesome tribute which the nation pays to the color line.) Why is mob murder permitted by a Christian nation? What is the cause of this awful slaughter? This question is answered almost daily – always the same shameless falsehood that “Negroes are lynched to protect womanhood”. (This is the never-varying answer of lynchers and their apologists). All know that it is untrue. The cowardly lyncher revels in murder, (then seeks to shield himself from public execration by claiming devotion to woman). But the truth is mighty and the lynching record discloses the hypocrisy of the lyncher as well as his crime. The Springfield, Illinois, mob rioted for two days, the militia of the entire state was called out, two men were lynched, hundreds of people driven from their homes, all because a white woman said a Negro assaulted her. A mad mob went to the jail, tried to lynch the victim of her charge and, not being able to find him, proceeded to pillage and burn the town and to lynch two innocent men. Later, after the police had found that the woman’s charge was false, she published a retraction, the indictment was dismissed and the intended victim discharged. But the lynched victims were dead. As a final and complete refutation of the charge that lynching is occasioned by crimes against women, a partial record of lynchings is cited; 285 persons were lynched for causes as follows: In Paradisum / Walk Together Children | (Libera Me) (cont’d) Is there a remedy, or will the nation confess that it cannot protect its protectors at home as well as abroad? Various remedies have been suggested to abolish the lynching infamy, but year after year, the butchery of men, women and children continues in spite of plea and protest. In a multitude of counsel there is wisdom. Upon the grave question presented by the slaughter of innocent men, women and children there should be…law-abiding citizens anxious to punish crime promptly, impartially and by due process of law… Time was when lynching appeared to be sectional, but now it is national – a blight upon our nation… Let us overtake the work of making the “law of the land” effective and supreme. Upon every foot of American soil – a shield to the innocent; and to the guilty, punishment swift and sure. May the Angels lead thee into paradise: |

Violin 1 | Schuyler Slack | Trumpet |